library(cowplot)

library(ggplot2)

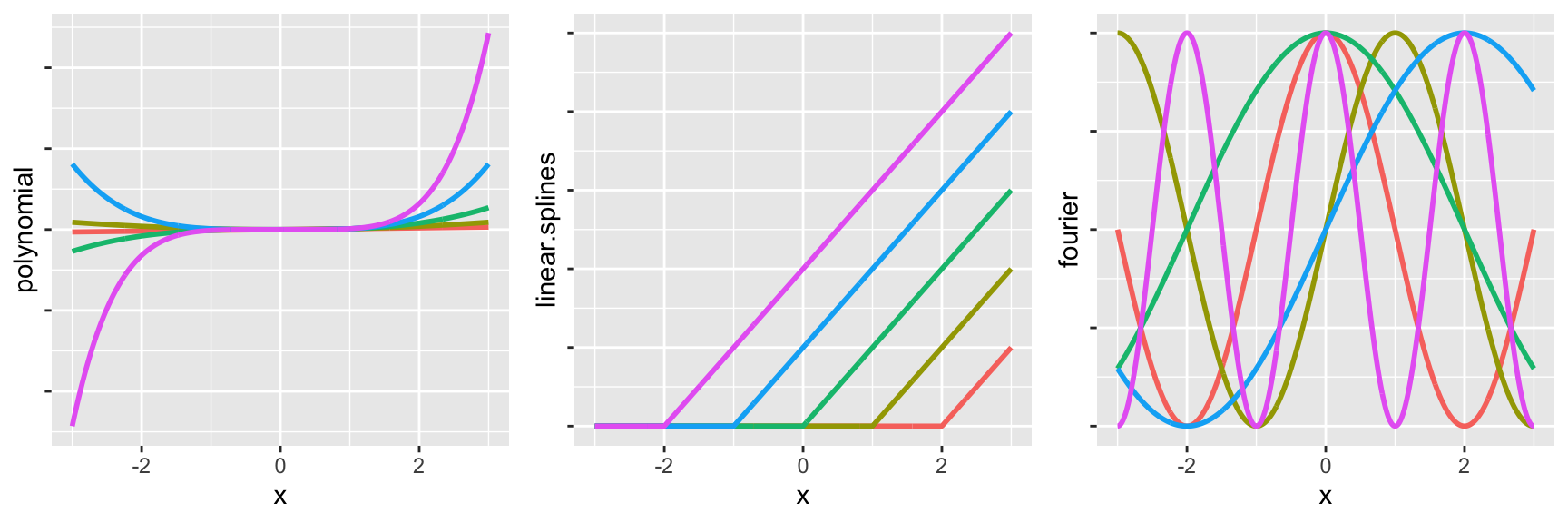

relu_shifted <- function(x, shift) {pmax(0, x - shift)}

# Create a sequence of x values

x_vals <- seq(-3, 3, length.out = 1000)

# Create a data frame with all the shifted functions

data <- data.frame(

x = rep(x_vals, 5),

polynomial = c(x_vals, x_vals^2, x_vals^3, x_vals^4, x_vals^5),

linear.splines = c(relu_shifted(x_vals, 2), relu_shifted(x_vals, 1), relu_shifted(x_vals, 0), relu_shifted(x_vals, -1), relu_shifted(x_vals, -2)),

fourier = c(cos(pi / 2 * x_vals), sin(pi / 2 * x_vals), cos(pi / 4 * x_vals), sin(pi / 4 * x_vals), cos(pi * x_vals)),

function_label = rep(c("f1", "f2", "f3", "f4", "f5"), each = length(x_vals))

)

# Plot using ggplot2

g1 <- ggplot(data, aes(x = x, y = polynomial, color = function_label)) +

geom_line(size = 1, show.legend=FALSE) +

theme(axis.text.y=element_blank())

g2 <- ggplot(data, aes(x = x, y = linear.splines, color = function_label)) +

geom_line(size = 1, show.legend=FALSE) +

theme(axis.text.y=element_blank())

g3 <- ggplot(data, aes(x = x, y = fourier, color = function_label)) +

geom_line(size = 1, show.legend=FALSE) +

theme(axis.text.y=element_blank())

plot_grid(g1, g2, g3, ncol = 3)